Chapter 3: Secret Weapons

Not only did I have a year to focus on my treatment and recovery. I also had a secret weapon: Child Life. I learned from the chemo snafu never to go to a doctor’s appointment alone. When Mark or a close friend or family member couldn’t go with me, child life colleagues and past students took turns accompanying me to appointments and treatments, making a mini party out of each and every chemo session. They brought treats, read aloud to me from trashy magazines and made me laugh so loud once that the nurse came to close our door so we wouldn’t disturb the other patients. And that was just the beginning of a landslide of help and cheer.

Each person performed a simple task or favor that woven together, formed an army of support. From walking to my dog, to teaching my course, offering to design a tattoo to beautify my scars and performing Reiki on me, their generosity knew no bounds. The regional group of child life directors organized the drop off of a slew of coping and comfort items, queasy pops, distraction toys to use during IV’s and blood draws, journals, chocolate, gag gifts, warm socks, and cute hats.

One friend’s actions were perhaps the most far reaching of all. Sydney, with her non-stop energy and raucous laugh. She blew me away when she organized Team Deb to walk in the American Cancer Society’s Breast Cancer Awareness walk, raising over $4,000 in my name. She sent every supporter a t-shirt that read “Team Deb”. Along with the shirt, everyone received a ridiculous Deb head on a tongue depressor, a disembodied photo of my smiling face. Those who couldn’t make the walk posted photos of themselves on Facebook wearing the shirt and holding the Deb head. Sydney showed up on the day of the walk with her whole family in tow. She jumped atop a park bench waving Deb head’s to help gather Team Deb amidst the throng of thousands. That sight is one I will cherish for years to come.

I wasn’t the only one in my circle to face the cancer battle. My colleague, Annie, experienced a double whammy. Two weeks after I shared my bad news, her sister was diagnosed with stage III breast cancer and had to endure a double mastectomy and heavy-duty chemo. Annie brought us together and we became chemo buddies, cheering one another on throughout the process. When Annie showed her sisterly support by shaving her head, they invited me to the shaving ceremony via video chat. I was moved to tears watching their husbands reverently shaving the heads of their wives. I had to turn away from my computer camera for a moment so they wouldn’t see me cry.

On my first day of chemo, I received a package in the mail: a life-sized cardboard replica of my favorite actor from Lori, a child life specialist and young mother in Colorado. I piggybacked on that idea and sent Annie’s sister a life-sized replica of Dwayne Johnson, or “The Rock”, his ring name as a professional wrestler and her favorite actor of all time.

For my last day of chemo, Annie decorated a graduation cap and gown with bandaids spelling out “Chemo Grad” for me to wear on the final day of treatment.

Tony, a newfound friend and colleague, offered me up his beach house on the Jersey Shore, saying, “If you ever just need to go and scream at the ocean, it’s there for you.”

But it didn’t stop there. Alumnae made me inspirational videos that brought me to tears. They sent me their own versions of Katy Perry’s “Firework!” with them dancing and lip synching to the uplifting lyrics. Sydney acted out the song “Roar!” with her kids, holding up signs that clocked each plot twist I’d encountered as she danced and pretend boxed with her two sons. On another occasion, she donned a Batman mask and videoed herself growling curses at cancer. When the video came through in a text on my phone, I almost peed myself laughing. These unexpected gifts lifted my morale on many rough days.

Annie and her sister appeared dancing and singing in their Firework video. I called to thank her and to see how her sister was faring.

“She has been so down in the dumps, she can barely get out of bed,” Annie confided. “ But making this video not only got her up and moving; she was able to raise her arms for the first time since surgery.”

It moved me deeply that a gift for me could be a gift for her sister at the same time. I was beginning to feel the power of community in unforeseen ways.

Close friends fought their own fears for me as they did their best to bring me good cheer. They showed up in large and small ways throughout my ordeal, when I needed to be distracted, witnessed, or when I just needed a good cry. Their love carried me along a river that flowed both sluggishly one moment and white water out of control at the next turn.

I didn’t take any of this support for granted. I knew full well how many people face cancer alone. It felt like an embarrassment of riches to have so many people in my corner. I wondered many times why I should be so blessed, while others should suffer in solitude. And I honestly worried that writing about it all might make some readers feel sad for not having this kind of support. But it also didn’t feel right to leave out the details of these small and large acts of caring. If only to describe all the many tiny acts that make it all bearable. You don’t always have to know what to say to someone who is ill, as long as you show them in some small way that you are thinking of them and carrying them in your heart. You are planting seeds of healing with each small act of kindness.

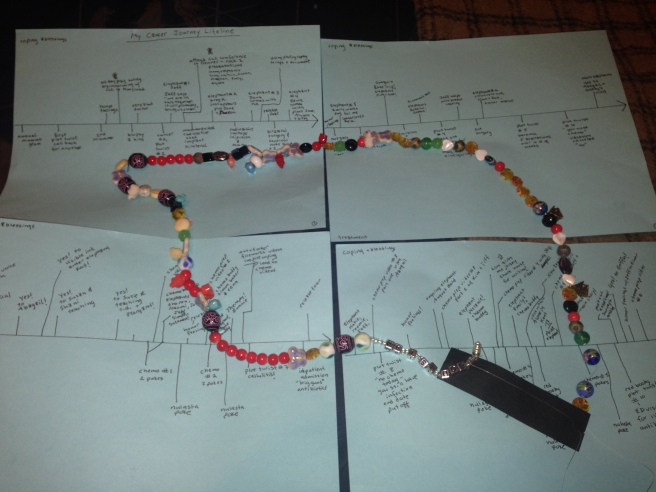

These invaluable seeds sprouted something equally wonderful and surprising. Other people’s thoughtful and creative interventions allowed me to tap into my own child life skills, which was my other secret weapon. Sheila sent me a precious box of beads, labeled in their various compartments. They are what we in child life call Bravery Beads or Beads of Courage. My friend added her own creative inspiration by including “coping” beads. I strung a bead for every procedure I underwent, every needlestick, every side effect, every scan and every damned plot twist. But I also added a bead for each coping tool I used and every blessing that came my way. I used tiny elephant shaped beads to represent each supporter who escorted me to an appointment or paid me a visit at home. I got this idea from Sheila, who said that I had a tribe of elephants walking every step of the way with me.

I strung a tiny house when I took Tony up on his offer and spent a much-needed weekend alone at the Jersey Shore. I didn’t scream at the ocean, but I did walk along its October shoreline and spent hours writing in a rocking chair on his front porch. I’ve always struggled with spending time alone, or traveling without companionship. Separation anxiety has plagued me since childhood, and it takes a lot for me to purposefully choose to be away from Mark overnight. This trip was a conscious attempt to face and wrestle with my fears. Cancer was making me brave. I didn’t know at the time that I was laying the foundation for some much broader adventures that followed in spades later that year.

I mapped all of this out on another child life tool, a Life Line. Just like a timeline in a child’s history book, I drew a horizontal line with an arrow pointing right on a piece of paper to represent the future. I separated the line into coping techniques and blessings along the top of the line, and medical treatments and side effects along the bottom. I marked each procedure, every side effect and plot twist. The process gave me a linear medical narrative of my experience. Along with the beads, it was three-dimensional proof that there was more good coming out of this than bad.

I’d come across the Life Line at a workshop run by the Play Therapy Training Institute in New Jersey years before. I demonstrated it in my play course each year, and it took root in hospitals via my students, bringing solace to many teens facing chronic illness. Natalie, a graduate of my play class, shared her successful use of the technique in an email to me.

Natalie met Rebecca, a 17 year-old inpatient, on her first day as a working child life specialist. Rebecca was quiet and kept to herself, but with a little coaxing on Natalie’s part, she made it to the teen lounge for a few games of UNO.

Following discharge, Rebecca visited hospitalized friends and frequented one of the support groups offered to the adolescent population. However, every time Natalie and she crossed paths, the teen seemed aloof and disconnected. Finally after about 2 months, Natalie found her alone in the teen lounge. She took a stab at building more rapport.

“You know, I’m not sure if you remember, but we met my first day on the job. We hung out and played UNO for like, an hour.”

Rebecca smiled at Natalie and said, “Yeah I remember.”

As it turned out, Rebecca was coming across as standoffish because it was her coping technique. She didn’t think Natalie remembered her, and she didn’t want to risk vulnerability by acknowledging their previous time together. From that moment on, their bond as child life specialist and patient solidified.

Right around November of that year, Rebecca began getting admitted to the hospital more than she would have liked. She saw herself as the caregiver of her friends, not the one who needed support. One night, Natalie noticed that Rebecca was visibly upset. She took a seat next to Rebecca’s bedside.

“I just wanted to check in and see how you are doing. I noticed you have looked a bit sad lately, and you are not leaving your room as much.”

Rebecca began to cry. Months of being admitted to the hospital had finally gotten to her. The doctors had told her that she would need a surgery. While the surgery was not life threatening, it would compromise her immune system.

“I just can’t picture myself ever living outside the hospital or having a normal life, EVER!” Rebecca’s shoulders shook with her sobs.

“It must be very frightening and lonely for you,” said Natalie. She knew better than to try to talk the teen out of her feelings, even though she fairly itched with the desire to give her a pep talk. Instead, she just listened.

A few days following her surgery, Natalie paid another visit to Rebecca’s room. During their conversation, it became clear that Rebecca continued to have a negative outlook on her health. Natalie gained more insight when Rebecca told her that she had lost a close relative to a similar diagnosis. Rebecca did not have an overall poor prognosis. But having lost a loved one, no matter what the medical team told her, she believed that she too faced an early death.

In child life, these are many of these deer in the headlights moments. A patient shares something that is almost unbearable to witness. Our initial response is an intense desire to rescue the person from emotional pain, in any way we can. We have to fight the urge to give false reassurance, or to talk them out of their feelings. In that moment, Natalie decided to try out a technique she’d learned in my class.

“Look, I know you’re not a fan of doing ‘child lifey stuff’ that you think is for kids. But I know you’re going through alot right now, and I just think it would help to lay it all out there. Just you and me. What do you think?”

Rebecca laughed and said, “Fine.”

Natalie replied, “Oh cool beans!”

Rebecca looked at her and said, “Cool beans?! Meg you cool, but you mad white!”

Natalie brought in paper and markers, but Rebecca preferred to just use a pencil. Natalie provided her with simple instructions for how to map out the defining moments of her life on a Life Line.

“Everyone has their own unique story. Different experiences come together to make us who we are in this moment.”

Natalie added that it was a way for Rebecca to look at her own journey, at the obstacles and accomplishments she’d encountered. Rebecca worked mostly in silence, asking for guidance a few times.

“There’s no wrong way to do it,” replied Natalie. “You can choose whatever memories fit”

Rebecca’s Life Line focused on life events around her health, and the health of the family member who had passed away. Her line only went to the middle of the page and stopped. The last thing that she added right before the end of her line was a dot for her 21st birthday. It was a month away.

“What happens after 21?” Natalie asked.

“Nothing,” she responded. “My 21st birthday is going to come and go, and I will be here like I always am, and I will die here. Nothing happens after 21.”

Natalie just sat with her in that moment. There didn’t seem to be any words that might add hope without negating the teen’s perception of her future. But before she left, Natalie reassured her that her future was hers to own, that she could add any possibility to that Life Line. As per Rebecca’s m.o. , she rolled her eyes and laughed at Natalie. Natalie just rolled her eyes and smiled right back.

The next day, Natalie passed Rebecca’s room on her way to the teen room. She waved to Rebecca and kept going, but Rebecca summoned her back.

“Hey,” she said, “Do you think you could get together with social work and figure out how I can get my G.E.D?”

In that moment, Natalie wanted to jump up and down and cheer and cry and celebrate. Reigning in her emotions, she said, ‘Yeah, totally, no problem.” Outside the room, Natalie ran down the hallway and knocked on the office door of the social worker. Excitement and hope pulsed in her veins and she couldn’t wait to share . Rebecca wanted to live. She wanted to have a future.

A few days later Rebecca was discharged. Her birthday came and went , and months passed. Before Natalie knew it, summer had arrived. She walked down the street after work, enjoying the warm breeze on her way to the subway. All of a sudden, someone grabbed her from behind, clasping their hands over her eyes. She screamed and turned to see Rebecca with one of her friends. Rebecca enveloped her in a gigantic hug, her story tumbling out. She was doing well, taking care of herself and staying out of the hospital as much as possible.

Natalie grinned at her. “So glad to hear that! We missed you at the hospital prom this year.”

“Yeah well, it’s hard to make it to prom when you’re a full time college student.”

As I strung my own beads, and marked my journey out on my Life Line, I thought about the power of narrative. Whether in the form of a story, a string of beads or a written map, narrative provided structure and cohesiveness in the face of chaos. It gave me the chance to witness my resilience, to count the obstacles I’d overcome and the things I did to get through them. It gave me hope, just like it gave Rebecca hope for her future.

To prepare for the second surgery and a possible shift in body image, I made a plaster casting of my breasts as a legacy activity. Child life specialists use legacy activities such as casting to prepare children for an impending loss. My alums had long inspired me with stories of casting children’s body parts pre and post amputation. The students were courageous in their willingness to face their own fears in conducting such interventions, in order to lessen the trauma that children faced.

Sheila braved the unimaginable in her quest to help 11 year-old Joanie come to terms with the unexpected amputation of her hand. When the brunette, doe-eyed preteen awoke from surgery and found her hand gone, she wept in shock and horror. She’d been fighting a serious infection in her hand, but amputation hadn’t been discussed as a possibility prior to surgery.

“I didn’t even get to say goodbye to it,” she sobbed.

Sheila knew right away what she had to do. She tracked down the lab where the hand was awaiting testing, and found it in a jar, swimming in formaldehyde.

“The thumb was the only part unmangled enough to cast,” she told me. She used quick drying plaster to form a replica of the thumb and brought the casting back to Joanie. Joanie wept in gratitude and clutched the casting to her heart wit her remaining hand.

“I’ll never let this go,” she told Sheila.

I felt silly lying on the floor as Mark draped wet plaster-coated gauze over my chest, but I knew that I was doing something proactive to counter my fear of surgery. Dr. Fodor had warned me that the end result of the second surgery wouldn’t be as “pretty” as the first one. I had no idea what shape my breast would be in after surgery, how misshapen or dented. Mark’s willingness to memorialize my body as it was, even if that meant kneeling awkwardly on the floor with cold, dripping plaster, made me feel truly loved. So did his openness to my thoughts about getting a tattoo. He hated tattoos almost as much as he hated texting, but when I brought it up to him he was quick to say, “This is a whole different story. You get whatever you need to feel good about yourself.”

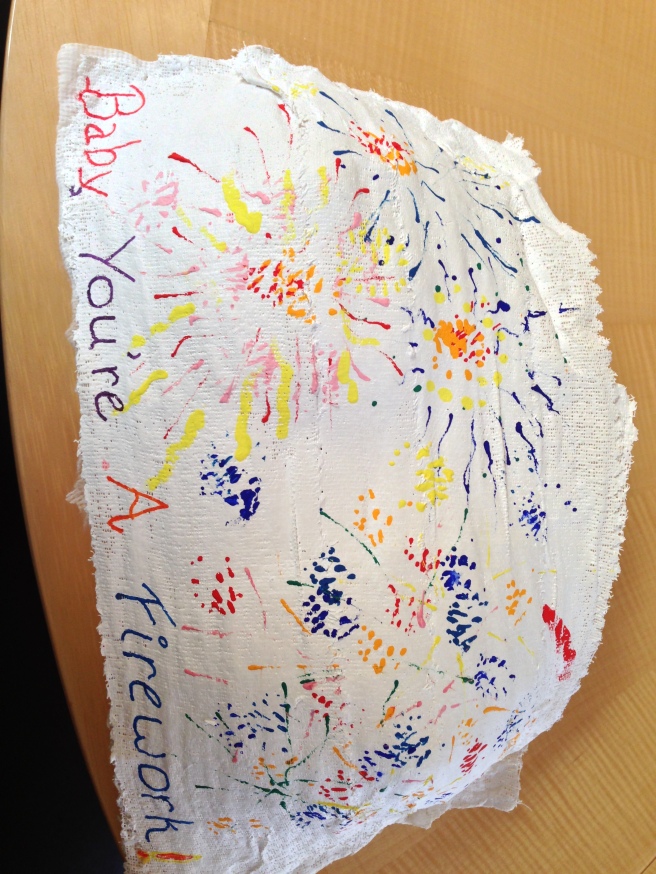

Once the plaster dried out, with the help of my fairy goddaughters Georgia and Adriana, I decorated the casting, painting bright fireworks onto the hardened material. The sisters were two of 15 children (yes, fifteen!) belonging to a friend of mine in Connecticut, where Mark and I had a country home. Beginning when they were much younger, they’d spent many summer weeks with us in the city, and this year was no exception. We copied a verse from Katy Perry’s “Firework” on the back of the piece, inspired by the music videos my alumni had sent me. Sometimes even pop music hits the nail right on the head.

“If you only knew what the future holds

After a hurricane comes a rainbow

Maybe a reason why all the doors are closed

So you could open one that leads you to the perfect road

Like a lightning bolt, your heart will glow

And when it’s time you’ll know”

Taking a cue from my students, I began to make my own music videos. I called them prep videos and used them to pump myself up before each chemo session and each week of radiation. I set up my laptop camera, and lassoed in friends and family when I could. I chose favorite songs, danced and sang, and acted out the plot twists of my treatment. In one, I acted out a puppet show to the hilarious refrains of Tom Lehrer’s “Masochism Tango.”

He perfectly described my love/hate feelings about chemotherapy when he sang, “Bash in my brain, and make me scream with pain, then kiss me once again and say we’ll never part.”

In another, I mimicked Rocky Balboa preparing for his boxing match, ducking and weaving, downing raw eggs, doing pushups and running upstairs. Okay, so I more like crawled up the stairs.

I wrote some of my own songs as well. Two were set to the tunes of Christmas carols.

My Journey of Cancer

Sung to tune of “Twelve Days of Christmas”

On this journey of cancer

The Universe gave to me

Three tiny tumors,

Bilateral surgery to remove them,

One post op infection,

An incision and a draining,

More surgery for clean margins,

A nasty seroma,

Five aspirations,

Eight rounds of chemo!

Recurrent cellulitis,

Three ER visits,

One inpatient admission,

And thirty sessions of radiation therapy.

On this journey of cancer

The Universe gave to me

Premier medical treatment,

Prayers from friends and family,

A newborn baby Godson,

Alumni videos on Youtube,

A one-year long sabbatical,

Writing coach for my book,

Coping beads of courage,

Access to a house on the Jersey Shore!

Companionship for appointments,

Team Deb walkers and supporters,

Clown Care visitation,

Child Life self-care techniques,

My own prepping videos,

And three weeks in New Zealand when I’m done!

Sung to tune of “Hark Yee Herald Angels Sing”

Hark ye cancer surgeons sing!

We cut out the whole dang thing.

And what cells we may have missed

Chemo’s poisoned dart hath kissed.

The linear excelorator now is wielding

Radiant beams of infinite healing.

Hark ye all survivors roar!

Life has so much more for us in store.

Hark ye all my loved ones sing

You’re carrying me through this entire thing.

Making these videos helped me to play with music and to maintain my sense of humor. Posting them on FaceBook helped my loved ones near and far know that I was okay. Perhaps my postings even inspired others facing my same battle. I never lost all of my hair, but it thinned considerably. I vowed to myself that I would avoid vanity and not hide my head, even on Facebook, but I didn’t always meet my own standards. It is not easy to look back at those images of my ill self now, but I am glad that I countered the shame with humor and transparency.

I also used humor and play to cope with each medical encounter. As a child life specialist, I’d seen countless examples of play transforming a child’s mood in the hospital environment. I remembered well the day that Steven lay curled in a ball beneath the covers in his hospital bed, his bald head hiding beneath the sheets. He had not showed up in the playroom that afternoon, which was unusual. This was one of those kids who waited eagerly outside the door each day for the playroom to open and was often the last to skate his IV pole back to his room at the end of the day. I had yet to see Steven without a smile on his round, open face. He was a content child with a quiet maturity that went well beyond his seven years. He took his medical treatment in stride and enjoyed the company of his brother and sisters, as well as just about every activity the playroom had to offer.

But not this day. It was mid-afternoon and we had yet to see a glimpse of Steven. His mother stopped by and informed me that Steven had an infection in his Broviak catheter and that it would have to be surgically removed. Steven was very upset and refused to leave his bed or talk to anyone. The removal of the catheter that allows patients to receive chemotherapy without an IV is difficult for any child. But it was important to find out what was upsetting Steven in particular. Understanding the details of what was causing this typically cheerful boy to retreat under the covers would give me a clue about what would help him cope.

With a soft knock, I entered his room and took a seat by his bed, beside his father. I gently coaxed him to tell me what was wrong. He was having none of it.

“We were wondering why you weren’t in the playroom today. Your mom told me that you have an infection in your Broviak.”

Silence.

“It can be pretty disappointing to have to go in for more surgery.”

Not even a nod.

“I am thinking that you might be too upset to even talk about it. So I was wondering if you could draw a picture about the most awful part of having your Broviak taken out. That way, I can understand a bit better what you are going through.”

I placed a piece of plain, white paper on the bed, along with some markers.

It took a few moments, but Steven uncurled from the fetal position and scooted up to a half-sitting position. He reached for a marker. I breathed an inward sigh of relief and sat back to see what he would draw. Placing his hand palm down in the center of the paper, Steven outlined it with a green marker. He still wasn’t talking, but he was communicating something important. He held out the drawing, and I took it from him.

“I see a hand outlined in green,” I said.

I had no clue what it meant. Steven’s father was the one who piped in with an explanation.

“Steven is mad because without the Broviak, he will have to have an IV in his hand. It hurts and it’s harder to play with an IV there.”

“Oh, I get it,” I said. “Yeah, having to get an IV is no fun. And having more surgery stinks, too.”

I paused to see if I was on the right track. He wasn’t speaking, but he was making eye contact.

“I do have an idea though.”

I continued, taking a chance. An idea had occurred to me and I wanted to try it out.

“How would you like to make a big mess that you don’t have to clean up?”

A tiny smile appeared on Steven’s face.

“Okay, then. I am going to set something up and let’s see what a big mess you can make.”

Stepping out into the hall, I headed for the utility room on the unit. On the way, I snagged Steven’s nurse .

“We are going to make a bit of a mess, but I promise I will clean it up,” I assured her.

She had no complaints. I gathered supplies for what I had in mind: one bedpan, a roll of toilet paper, a large piece of chart paper, tape, and an armload of towels and sheets.

Reentering Steven’s room, I stopped at the sink to fill the bedpan with warm water, placing the filled bedpan on Steven’s rolling bedside table. The sheets and towels went on the floor against the wall opposite the foot of his bed. Steven’s eyes followed my every movement, showing curiosity and anticipation.

“So, here’s the deal.” I said. “Lots of kids have stuff happen in the hospital that they find upsetting or scary. Sometimes it helps to get these feelings out in a physical way. I am setting up a target game, where you will get to throw wet toilet paper at what is upsetting you until it is completely destroyed. The question for you now is, do you want to destroy the drawing of your hand, or is there some other thing you could draw that you’d like to obliterate?”

Steven picked up a marker, so I brought over the big piece of chart paper. He got right down to work, drawing a huge needle that took up the entire sheet of paper.

“Oh,” I said. “That looks like the needle that might have to go in your hand.”

He nodded. When he finished, I took it from him and taped it on the wall opposite his bed.

“Now for the demonstration,” I said, reaching for the roll of toilet paper. “See, you take as much as you can to make a nice, big wad.”

I unrolled it from the tube, wrapping it around my hand.

“Now, here’s the most important part. You dip it in the water, but you don’t squeeze any of the water out, so it’s sopping wet.”

Steven was riveted.

“Throw it as hard as you can at the target, yelling what makes you mad or scared.”

Winding up my arm like a star pitcher, I let go of the wad.

“I hate needles!” I yelled.

As my voice filled the small room, the toilet paper thwacked solidly against the drawing of the needle, sticking there a moment before falling to the floor. I turned to Steven.

Steven sat straight up and reached for the toilet paper roll. He followed my actions, and as he whipped his TP bullet at the target, his voice rose to a throaty yell.

“I hate IV’s!”

I applauded him and he took it from there, yelling out the things that had been bottled up inside, until the chart paper sunk to the floor in defeat. For the last few tosses, he rose to his knees in the bed and used his whole body to fling the wet mound at the target. It took a while to clean up the stray clumps of sticky toilet paper and mop the floor with towels, but I didn’t care one bit. Steven was now talking animatedly with his dad and he ended up in the playroom not long after.

Knowing how powerful play could be, I sought ways to incorporate it into my everyday life. I pressed a button on an electronic toy that alum Lesley gave me, emitting cartoon sound effects whenever I got a needlestick. I brought fake vomit to a chemo session and rang for the nurse, complaining of nausea. She laughed and said that my grin had given me away.

“You look far too happy to have just thrown up!”

I carted my six-foot tall cardboard replica of Simon Baker to appointments and tweeted him a selfie of us in the subway. I asked doctors to throw Mardi Gras beads when they wanted to examine my breasts for the millionth time due to recurrent cellulitis. I wore my Hello Kitty hat to radiation treatments.

I purchased toys over the internet and couldn’t wait to blow up my very own bop bag, a Bozo-the-clown replica. Nor could I resist a game advertised as “Doody Head”. It consisted of two hats festooned with targets and velcro. Players took turns tossing fake poop at one another, seeing who could score the most points by catching the poop on their cap. I bought a Batman mask and cape and dressed up to join a friend and her 5 year-old daughter for trick-or-treating on Halloween. I carried a tiny playschool clown in my purse that a clown friend had given me. I also carried a farting keychain that emitted horrifying noises whenever I set it down anywhere.

When I received the book of Creative Cursing from Natalie, I flipped through the book each day to choose a curse of the day. On my last day of chemo, I wore my graduation cap and gown and handed out pink cupcakes to everyone in the waiting room. I marched back to the chemo room to Pomp & Circumstance playing on my iphone, and I danced out to “Hit the Road, Jack!”

With 18 weeks of chemo under my belt, the marathon of radiation treatment began. I created a playlist on my phone of songs all about fire, heat and radiation. I plugged into this when I walked to and from 30 radiation treatments over a period of 6 weeks. I turned up the speaker and played them while I was laying arched and exposed on the linear excelorator as the machine zeroed in on my chest with its power.

“Welcome to the new age, to the new age. I’m radioactive radioactive!”

Writing was another coping mechanism. Early on in my treatment, I had a chance encounter that led to something amazing. Awaiting a pre-surgery procedure in a tiny alcove, I looked up to see Chris, a colleague I had known for many years. He was the librarian for the Patients Library, and he was checking to see that there was an ample supply of magazines in the waiting area.

“Deb Vilas! What are you doing here?” he said.

“I’m a patient. I have surgery tomorrow. Can you believe it?”

Just then, a nurse summoned me into the treatment room. I gave Chris a quick hug and promised to stop by the library after my procedure. An hour later, I entered the library, marveling at how it seemed the same after so many years. Bookshelves towered close to the high ceilings. A book cart stuffed with paperbacks sat in a corner, an oil painting of a donor gazing down at it. That wonderful smell of wood, paper and freshly cut flowers welcomed me and transported me back in time to childhood trips to our neighborhood library. Chris joined me at a small table amid the stacks and listened intently as I caught him up on my life and my new status as a cancer patient.

Chris’s energy had always been a pleasure to be around. A creative soul, he moonlighted as an actor in soap operas and wrote screenplays. We shared a love of the written word.

“So, I have one thing that you simply must do as a patient. I am the co-director of a program here called ‘Writing for Life.’ We take patients and survivors who are interested in writing, and we hook them up with published authors as writing mentors. This has you written all over it!”

Chris handed me a book.

“We publish one of these anthologies every year. You have so much to write about. This would be perfect for you. Take this and have a look, and when you’re ready, call the director of the program. She will have you writing by next week. And Deb, don’t let this cancer define you. You are so much more than a patient.”

As I left the hospital that day, I felt the first surge of certainty and joy at the thought of having something to focus on during my treatment. I was relieved to be on sabbatical, but to be honest, the thought of a whole year stretching out before me without work was daunting. Writing would structure my days and my energy. I wouldn’t be left floundering with endless empty hours, days and weeks ahead. In Chris’s words, I’d be more than a cancer patient. I would be a writer.

I enrolled in the program the next day and was paired with Diana. She visited me at home and gave me feedback as I began to write about my life’s work. Diana was perfect in that she told me my writing was great and then tore apart every piece and made me do rewrites until I grew beyond my own limitations. I knew I had a book in me, and now I had someone to help me pull it out, word by word. In addition to working on the book, with her help I published four professional articles that year, as well as the CLC survey and report on the State of Play in North American Hospitals and a chapter in the Writing for Life Anthology. I met every deadline without fail. It was a time of outrageous creativity for me. The cancer forced me to step away from my hectic life, and beneath the surface was a geyser that once tapped, kept spouting. I couldn’t stop writing if I tried.

All of these pieces, the writing, the beads, the videos, the loving presence of everyone, my humor – they all wound together to form a beautiful tapestry of coping. Cancer itself wasn’t fun, but there was a certain magic to the components of this new reality. I had no choice but to focus on my body and its healing process. My body and mind resonated with energy and focus in a way that I had never experienced before. Now when I lay awake many hours at night, it was rarely unpleasant. I contemplated my life, where I had come from and where I was heading. I also went back into psychotherapy, part of my self care routine that gave me a safe place to process all that my psyche delivered into consciousness. I had the time and space to examine some of the hard questions and unresolved issues that surfaced.

But one thing that I never asked was, “Why me?” Long before my personal brush with mortality, when I worked with children who died way too soon from cancer, I’d sought solace in a book called Why Bad Things Happen to Good People” by Harold Kushner. The book helped me to make sense out of what seemed like senseless loss and suffering. I had come to the belief that our God was not a punishing God, and that pain and sorrow are as much a part of our lives as are joy and love. I believed that everything happened for a reason. I know this is not everyone’s belief, and that saying this to someone facing illness and loss can be both shaming and minimizing. But it had the opposite effect on me. I was now determined to make the most of my experience, to use it to deepen my connection to God, my family and my community. If I was lucky, maybe someone else could get something out of watching me go through this with humor and dignity, the way I had been inspired by every kid with cancer I’d ever worked with.

beautiful Deb!

LikeLike

Thank you Maryanne! I still hesitate to write about the support and coping, as I know many people might be put off by it, especially those in the middle of the struggle. There is a great blog that addresses the challenge of being confronted with inspiring stories when you are doing your best to just get up in the morning. But this is what helped me, and I hope it gives caregivers some good ideas at the very least.

Love to you!

LikeLike

Wow, this is the best one yet! So beautifully written. And how you remembered every step is beyond me. A fantastic job.

Love, Jeff

Date: Wed, 24 Feb 2016 19:45:44 +0000 To: jmkrauss@msn.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are amazing Deb. what a voice you have. Thank you for sharing your story.

Maureen

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank Mo! It was such a crazy ride. Couldn’t have done it without child life!

LikeLike

I loved it!!!

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

Thank you Elizabeth. I love you.

LikeLike

Deb,

Thanks for sharing all the steps in your journey. Wow. So grateful to have you on this planet and keep writing!

Lots of love,

Liz

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Liz. That is only one third of the story, which continues with my post treatment adventures. I will keep publishing chapters, although I think I got over excited and made the last one way too long! Love to you and Quinn.

LikeLike

Aww, I absolutely love this!!! Team Deb all the way!!! Thanks for making me cry, in a good way! I am so proud of what you have accomplished!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Child Life Mommy and commented:

When a child life specialist goes through treatment for breast cancer, she leans on her supportive community of family, friends and child life colleagues to help her cope. I am so proud to have been part of Team Deb!

LikeLike

Inspiring to read Deb, and I don’t think many would feel as though their own situations are minimized. Most of us do what we can with whatever we have, and you have a lot of great supporters who love you, wonderful experience to draw on, a creative mind, and determination. I applaud you! Bindy

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Bindy! I am now in the position of doing my best to support a dear friend going through what I went through. I am now feeling what it is like from that side and even more thankful for all the care and support I received and continue to receive. Love makes the world go round……

LikeLike