I am wondering how many people out there are feeling a bit broken these days. Whether you are parents, teachers, child life specialists, essential workers, or caregivers, whether you live alone or navigate relationships and conflicting needs at home amidst the pandemic, are there times when you feel — well — certainly not at your best?

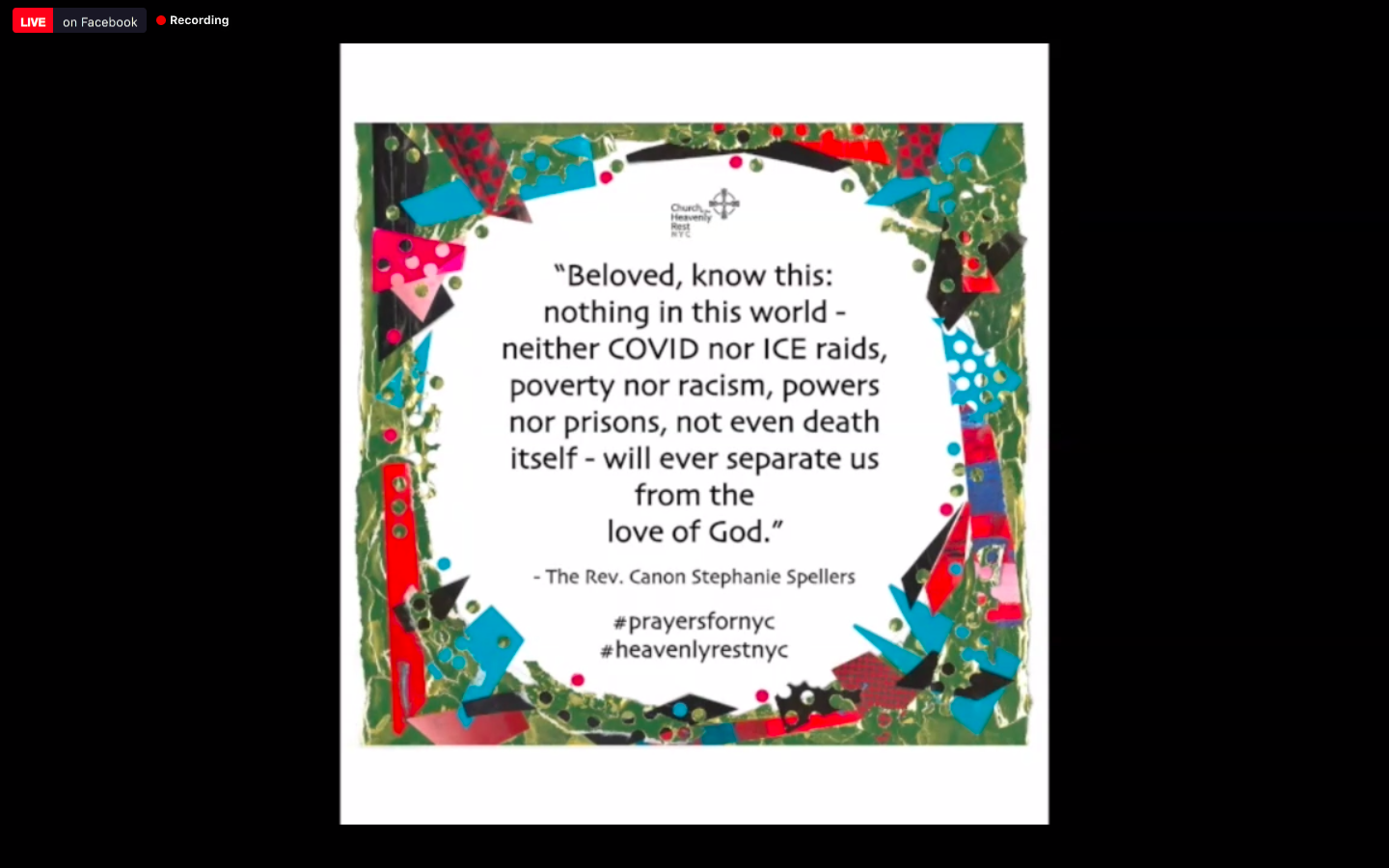

Monday was a day like that for me. I was following my typical morning routine that involves prayer online with the Church of the Heavenly Rest. I settled onto my couch and lit a candle while my laptop booted up. I signed into my email and clicked on the Zoom link for the video connection …… and all I got was an ERROR message. Thank God I was quickly able to find a workaround. I dialed in with my phone while I reached out via email to Lucas, the program organizer at the church, and simultaneously tried another browser. I was into the service in a minute or two. You would think that I might feel accomplished at this feat of multitasking, but here is the thing. Even though I was functioning and problem solving in real time, I was also bawling my eyes out, with all the unleashed vigor of a toddler.

And I cried so hard that there was no way I could turn on my video or microphone once I got into the service. I think I scared my dog too.

Since the pandemic began, I have only missed one service, and that was for a medical appointment. Amidst the tears yesterday, I was struck by how dependent I’ve become on the routine and comfort that morning prayer provides me: the reverend Matt’s steady, soothing and cheerful presence, the stalwart group of parishioners, who, like me, show up every day, helping one another carry our collective burdens and celebrate our joys. The predictability of the liturgy.

In that brief moment of disconnect, I felt panic at the thought of not being able to join in the service. The panic was followed by a crushing wave of grief, all out of proportion to the situation, but greatly indicative of the accumulated losses of these past 5 months.

The misery of the moment didn’t dissipate. It sucked and pulled at me like quicksand for most of the day. It wasn’t until late afternoon that the despair began to lift. But I can see the seeds of recovery planted throughout the day, some even in the midst of my emotional tornado. The kindness and speed with which Lucas responded to my distress. A chat with a friend midday. In the early evening, another daily ritual, FaceTiming my parents. Our conversations are as predictable as liturgy – we share the highlights of the day, whether or not my folks went for a drive to their local farm, or my dad went for a walk. We ask one another what we are having for dinner, I ask what wildlife they’ve seen, and my dad tells me a bad joke that he saw on the internet and memorized just for me. My mom busts my dad’s chops for hogging the phone, and then joyously exclaims, “There you are!” when he turns the phone her way so that she can see me.

These conversations are the glue and ballast that hold me together.

But there’s more to it. After I wished my parents a good evening, a friend called me and asked if I could spare some time to listen to her about the hard day she’d had. While I listened, nursing a cup of tea, I remembered what Matt had said earlier that day, that when people are struggling, they don’t always need advice. Sometimes, the listening, the gentle witnessing, and just asking the right questions is the way to go, so that our loved ones can access the answers within themselves.

Later in the evening, the phone rang again. This time, it was a child life colleague seeking some support as she prepared for a radio interview. After we discussed her plan of action, she went on to share some great stories of how she has been using Loose Parts to help hospitalized children make meaning out of their medical experiences. When I hung up the phone from these conversations, the change in my mood was nothing short of remarkable. How could it be, that during such a low day, when I felt so beaten down and miserable, the universe could make such good use of me? If loose parts are what children need to make sense of their suffering, it seems that encounters with others, be they friends, colleagues, family or strangers, can serve as our loose parts. Our mutual conversations and witnessing can bring solace, perhaps a shift in perspective, and sometimes even an answer or two. The amazing part is that we don’t have to be at our best to show up and make a difference.

I have a porcelain angel who has knelt in a state of constant prayer on my bedside table since I was a small girl. She is somewhat worse for wear, battered, stained and the tips of her wings broke off years ago. But she brings me comfort every night.

It’s not just how others shore us up when we stumble. It is how even in our brokenness, we can be the glue and ballast for others, and in doing so, burgeon our own healing and open our hearts to the presence of a love beyond our understanding in the midst of our suffering.

For your listening enjoyment, click on the link below.