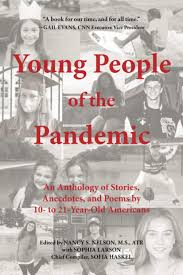

Nancy S. Nelson, MS, ATR, had a vision one week into the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. As she grappled with her own response to the surging COVID numbers and the lockdown in her home in NYC, she realized that children might have an even tougher time than adults coping with the pandemic. As an art therapist working in hospitals and private practice, Nancy had always known the importance of giving voice to children and youth through artistic expression. Now it felt like the right time to gather in the stories and words of children living through a vast disruption of their lives.

Not only did she gather over 125 submissions (over 40,000 words!) in four months — She also made leaders out of young people, hiring college students to gather, compile and assist in the editing work of this volume. From personal and professional contacts, Nancy established a core group of eleven 10-21 year-olds. Her request for participation in the book was a simple one.

Write two pieces in three months about what you experienced during the pandemic, and get two friends who live in other states to do the same.

The result was an incredible collection of voices from all over the country. Nancy holds deep admiration for the children and young people who were able to create even in the midst of so much loss and stress.

I realized that it was not mere writing talent that the contributors presented. It was their courage and honesty in being able to participate during such a tumultuous time in their lives.

Here is an except from the book by Maya Tuckman, age 14.

“All I Know

The world is changing drastically in ways I do not completely understand. Adults say we are living through a part of history, but we cannot predict what the future will bring, just like how I know who I am now but not who I will become. All I know-all that I can know-is the heat of my breath on my face under a cloth mask, fogging up my glasses; the whirring of my laptop computer in online classroom sessions, a sea of my classmates’ faces, in their homes, in hoodies and pajamas; the sound of my younger brother’s laughter and cheers, muffled from his bedroom, which he hardly leaves, as he plays video games with friends he can’t see; the gloves and mask that my Granny wears when cautiously visiting our house. I recognize that I am privileged to know these things. There are students whose educations are falling behind because of lack of access to both physical classrooms and digital resources. There are kids whose parents must leave the house everyday for work, potentially exposing themselves to the virus, but my parents work from home. There are the homeless, with no shelter to shield them, and those who live alone, with no one to keep them company. And then there are those who work on the front lines, in hospitals. Who are constantly overworked and overstressed. For me, some things have stayed the same. Like the smell of wet grass after the rain, the sound of the singing birds that flit about the trees. But I know other things won’t ever be the same. I know I will have to adapt and stay vigilant. So I hang on to the hope that the future will be brighter, even if things don’t look the same as they used to.”

And yet some things remained the same…………………

This book is a gift to all of us, the voices of those who will inherit the post-pandemic future. It is a call to all of us to do our best for these young people, to care for the earth and one another so that they can live into the possibilities we have only dreamt of.

To enter our give-away of an ECOPY of the book, please leave a comment on this blog, repost this blog in social media and tag #youngpeopeofthepandemic and @pediaplay.