Source: Taking Medical Play to a new level with Parker, Your Augmented Reality Bear

Uncategorized

Spotlight: Child Life Intern in Community-Based Practice

This week, I will spotlight a Canadian career changer as a guest blogger. Kim Zink is currently completing her child life internship in a community-based practice with mentor, Morgan Livingstone, a CCLS based out of Toronto, Ontario. Kim left her position in the school board to focus and refine her scope of practice to assisting children and families facing challenging life events. She sensed the need for more psychosocial supports and greater visibility of child life services in the Ottawa region. So, with the support of her husband, two children, and extended family, she is chasing her dream!

This internship has been the perfect fit for me. My mentor has been working in her own practice for many years, so she has a broad network of community resources and wealth of knowledge in many areas including global health, retinoblastoma, and traumatic brain injuries. She also wrote an incredible parent guide for families affected by breast cancer (including metastatic disease).

My internship has been full and rich. My first rotation took place at the Shoe4Africa Children’s Hospital and the Sally Test Pediatric Centre in Eldoret, Kenya. Morgan has been developing a self-sustained child life program there for many years. It was invaluable to see the robust program which now includes a number of child life specialists, teachers, playroom monitors and child life assistants. The team endearingly refer to Morgan as ‘ our mwalimu,’ which means teacher in Swahili. Morgan served as an example of how to be patient-centered and culturally sensitive in global healthcare, no easy task.

While we were there, I was invited to sit in on an oncology meeting. It was deeply moving and inspiring to hear the doctors speak so highly of the child life staff to the families. The doctors spoke of being a team and that families should refer to child life with any questions about their child’s developmental, social and emotional needs. The child life team has built an advanced practice and a great interdisciplinary approach. Unfortunately, in some areas, the pain medications and ideal supplies are not available, so I had the opportunity to offer distractions through games on a tablet and meteor storm toy to bring the child’s attention away from the burned areas and bandage changes during procedures. It was a proud moment for me when the doctor told me that the best bandage change a particular boy had ever had and that I was welcome back anytime.

The hospital sees over 300 children every day, and sadly many of the children are not brought to the hospital until their illness has progressed to the palliative state. So we turned our focus to legacy building and adding quality to end of life. One simple and inexpensive legacy activity that worked well was making a salt dough handprint for each family.

During my second rotation, I relocated to Toronto to intern in Morgan’s local private practice. She sees a number of teen patients, which was a demographic I knew I needed more experience with. I discovered it’s key to listen carefully to their interests and then go home and study up on these interests to gain common ground for future conversation and show teens that you listen and care about what they have to say. So now I know more about the ins and outs of making slime and the youtube channel, Simply Nailogical, than I ever thought possible. This research paved the way to building rapport and trust with one teen in particular. Showing interest in her interests was a great connector.

My future work in child life has also be enhanced by working with my mentor on traumatic brain injury cases. I had the opportunity to see treatment plans, do home visits, sit in on team meetings, and understand the billing process through insurance providers. During a recent conference call, a teen’s mother said, “Things started to finally turn around when Morgan was added to the rehab team and started her sessions. She [the teen] found the tools and started to cope, she really improved with Morgan’s help.”

My latest adventure in my internship included a trip to Washington, DC for the One Retinoblastoma World Conference. I had the privilege of assisting Morgan with the child life programming, which included transformative literacy, medical play, and lots of activities with special eyes. It was great to see one child move from fear to familiarization with the sedation mask. Another child displayed new skills of mastery by using the medical doll to practice cleaning and adjusting an ocular prosthesis. Still another young child spoke openly about having a special eye, as he called it, for the first time. One of the teens overheard and said: “Me too, and I like to take mine out with a suction cup.” There is nothing like these spontaneous conversations to bring about that reassurance of ‘sameness” and soothe constant feelings of being different from everyone else.

Above all, I will finish my internship with ample understanding of what it means to be an advocate for children. Morgan is a tireless champion for her patients, working to be sure they have everything, from a great relationship with their general physician to the correct supports from their school. She moves mountains to make sure the children and teens in her care have everything they need to be happy, healthy children. We need more child life specialists doing this work in the broader community.

PS: Navigating independent and Canadian internship possibilities has its challenges. I highly recommend the Facebook group for ‘Child Life for Canadian Students’ and http://www.cacll.org/

How to talk to kids about the Las Vegas mass shooting

I have no words, so today I reach to Katie Kindelan for hers. The following is reprinted from ABC News website

By KATIE KINDELAN

When Vickie Nieto digested the news this morning that at least 58 people died in a mass shooting in Las Vegas, the first thing she thought about was what she would tell her two daughters, ages 10 and 14.

“My 10 year-old heard about it on the TV before school,” Nieto, of Land O’ Lakes, Florida, told ABC News. “I didn’t want to tell her about it because I didn’t want to scare her.”

Nieto said her fifth grade daughter is “already scared about school shootings because they have to practice for them at school.”

But this morning, many people like Nieto woke up to the news of a mass shooting at the Route 91 Harvest Music Festival in Las Vegas, where a gunman opened fire on a music festival crowd, starting just after 10 p.m. local time Sunday. At least 58 people were killed and 515 were injured.

In the wake of the shooting, the Las Vegas Police Department said authorities responded to a hotel room on the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay hotel, where police said the suspected gunman, 64-year-old Stephen Paddock, was dead. Police said they believe Paddock, of Mesquite, Nevada, killed himself prior to police entry.

Many parents and caregivers were faced with conversations about the mass shooting even before children left for school.

“”‘Parents should let their kids know that, ‘I’m here to answer any questions you may have, any worries you have we can discuss,”

For others, the conversation about the tragedy could begin when kids return from school, after they may have heard about the shooting from classmates or teachers.

“It’s important for parents to start the conversation,” said Robin Gurwitch, a psychologist at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. “As much as we would like to wrap our arms around our children and try to keep anything bad from getting through, it’s unrealistic that we have that ability.”

Gurwitch, also a member of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, said that the conversation parents have with children should be age-appropriate.

For children old enough to understand what happened, parents should focus on letting them know that they are not in specific danger.

“Help them understand that there was a shooting in Las Vegas and many families were out listening to music when somebody, for unknown reasons, started shooting people,” Gurwitch said. “And tell them that because the police responded so quickly [the suspected gunman] is no longer a threat.”

Dr. Lee Beers, a pediatrician at Children’s National Health System in Washington, D.C., said a tragedy does not have to be a trauma for children if it is “buffered by good, strong and caring relationships, by the adults around the child.”

She also recommends different responses for different ages, and individualizing the approach for each child.

Preschool age: This is a time when parents have a high level of control over what their children see and hear so it does not need to be brought up unless a child hears about it first. In that case, Beers recommends making sure the child knows you are there to answer any questions.

Elementary school age: This is an age when parents should preemptively help their child know about the tragedy and share basic details and leave the door open for them to ask questions, according to Beers.

Middle and high school age: Beers advises having a more detailed conversation with children. Start by asking questions like, “Have you heard about this?” and “What do you think about this?” to find out what they know and what may be bothering them.

In the Las Vegas shooting, videos taken by onlookers and shared on social media gave a glimpse of the chaos during and after the shooting.

“So hard to raise a child in this country these days,” posted one mom on Facebook. “There doesn’t appear to be anywhere that’s safe.”

Gurwitch said the visual aspect of the shooting should give parents even more of a reason to speak with their children openly and candidly, according to their ages.

“Parents should let their kids know that, ‘I’m here to answer any questions you may have, any worries you have we can discuss,’” she said. “Check in at the end of the day to see what their friends were talking about at school and what they saw on social media so they have an idea of where they’re starting from and how to continue the conversation.”

Seeing frightening images repeatedly can be traumatic for children, so talking about the images and limiting exposure to them can be important.

“Repeated exposure to viewings really does increase the stress and trauma in your emotions, in the way that you respond to it,” Beers said. “It’s very tempting to watch the coverage 24-7 so I think really self-limiting that is really important because that repeated exposure escalates the emotions and escalates the feelings.”

Nieto said she recognizes how upsetting the images on TV and social media can be.

“It’s terrifying for me and I’m an adult,” she said. “It’s very terrifying for kids to see it.”

“”“Acknowledge that there may be a little bit of extra help that is needed …

Nieto said she “always has conversations” with her daughters about tragedies like today’s, but is struggling for what to say in the wake of yet another shooting.

“This is very upsetting for them to have to hear about this again, because it happens all the time now,” she said.

Older children in particular may have concerns because the Las Vegas concert shooting happened so soon after the May 22 bombing at an Ariana Grande concert in Manchester, England, killed 22 and left more than 100 injured.

“Parents who are up front with their kids about these kinds of things, their kids tend to do better than parents who try to hide these things,” she said. “Talk about safety issues and what we do to keep our families safe, what we do to keep each other safe and what communities do to keep us safe.”

Both Gurwitch and Beers advised parents find ways they and their children can help those affected by the shooting, like first responders.

“Little children can draw pictures and older children or teens can write letters,” Gurwitch said. “Sending these to Las Vegas Police, EMS, Fire and/or local responders to thank them for what they do every day can help children feel that they have taken a positive action and the boost to responders is priceless.”

Nieto described one reaction she had to the shooting as being scared to “go anywhere” out in public.

“It terrifies me to even go to the store, especially with my children,” she said. “Because you never know who has a gun these days.”

Gurwitch shared language parents like Nieto can use to reassure both themselves and their children that it is safe to continue life as normal, while being alert to safety issues.

She recommends parents say something like: “I also know that there are a lot of people that this is their job to keep us safe, so I’m going to continue to do the things that we like.”

If parents and caregivers notice children are overly worried or having trouble focusing at school or at home, Gurwitch said to not delay in reaching out for help, and to have patience.

“Acknowledge that there may be a little bit of extra help that is needed with homework, care and attention around bedtime, and that’s true for younger children as well as teenagers,” she said. “If you don’t know what to do or what to say, there are people you can turn to ask what you can do for your child.”

Gurwitch and Beers recommend as resources for parents, the American Psychological Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, school counselors, family physicians and local mental health counselors.

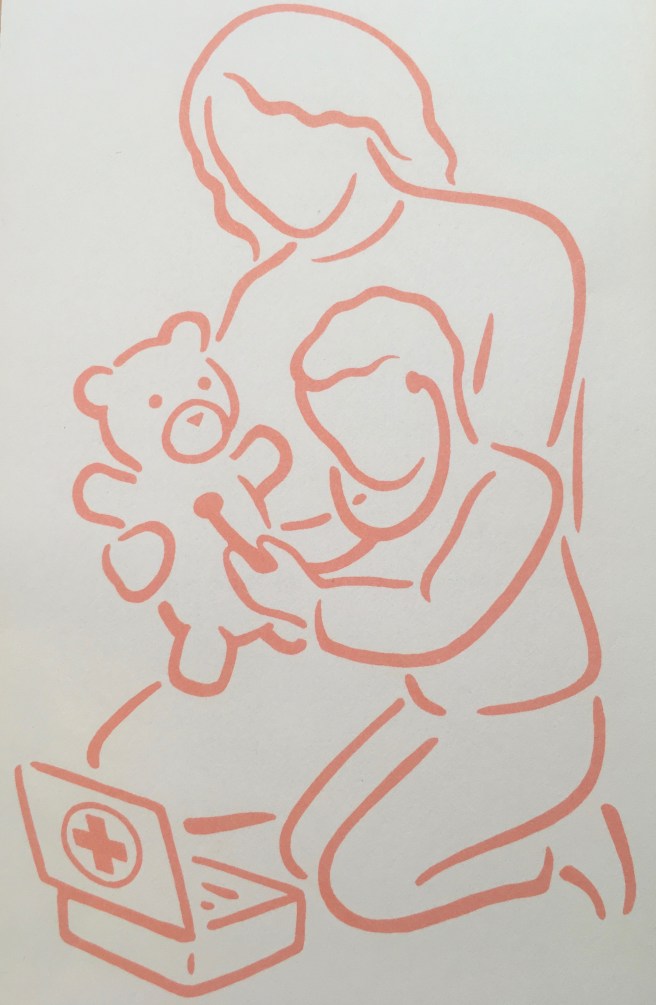

Child Life in Private Practice: Supporting Parents and Children through Medical Encounters

Studies show that children who are prepared for medical procedures recover faster with less emotional stress. Even routine procedures such as vaccinations can cause children undue stress and lead to treatment noncompliance and avoidance of medical care. Children require developmentally appropriate information about what they will see, feel, hear, taste and smell that will prepare them without overwhelming them. Through hands on demonstration and guided play, I can prepare you and your child for medical encounters, and coach you both in coping strategies. Calm, informed parents are the best support for their children when facing routine and unexpected medical visits and hospitalizations.

I am pleased to announce the expansion of my private practice as a Child Life Coach on the upper east side in Manhattan. Child life specialists are trained in child development, education, anatomy, health care systems, family systems, ethnocultural issues, advocacy, and bereavement. In and out of hospitals, we help children and families prepare for and adjust to medical encounters by providing education, medical play, support, coaching and advocacy.

Here are several of the services I offer to parents & schools:

- Coaching and Support for Parents in::

-

how to prepare their cildren for medical events, from routine wellness appointments to surgery or long term treatment.

-

how to support siblings when a child is ill

-

how to support children through a parent’s serious illness.

-

Child centered play skills to caregivers who wish to connect more with children in this digital age.

-

In home preparation for elective medical, diagnostic, and surgical procedures.

- Workshops: Please see my listing on Cottage Class Parents As Heroes: Supporting Children Through Medical Encounters

-

- Professional Development: Training and Support for Teachers

-

How to support your class (school) when a student faces illness and loss

-

Child-centered play techniques

-

Emotionally responsive teaching

-

State mandated child abuse detection and reporting

-

- Video Conference Consultation and Support

- If traveling is an issue, I am available through video chat to support parents at a distance

More information about my practice can be found on my website at debvilas.com, and please take the time to like my FaceBook page at Pediaplay

I greatly appreciate any referrals to parents and caregivers who need this kind of support. I can be reached at debvilasconsult@gmail.com

All the best,

Deb

Deborah Vilas, MS, CCLS, LMSW

CLC Video with Deb Vilas Appearance: That’s Child Life!

Child Life & Art Therapy in Disaster Shelters: The Humanity Factor

During these recent days of hurricanes, tornados, fires and violence, it is hard to know in which direction to turn – what to focus on – where to put our energies. Fred Rogers taught us all to “look for the helpers”, and I always find that calming and inspiring, so I have decided to republish a piece that I cowrote with Tara Lynch Horan after we coordinated services at a shelter in NYC following Hurricane Sandy in 2012. It gives a taste of what child life specialists and art therapists can do to ease the suffering of children in times of upheaval.

In addition, tapping into our ability to BE the helpers can also assist us in making sense of tragedy. In this vain, I attended a training this past weekend given by Children’s Disaster Services in coordination with the Child Life Disaster Relief organization. It was empowering, and I highly recommend the training to anyone who wishes to volunteer to provide safe play opportunities for children following disasters. You can do this locally or be deployed to other states in the USA. And if you can’t lend a hand, donations to organizations like these can still make a difference and impact quality of life for children.

Here is the article reprinted from Vilas, D. & Lynch Horan, T. (2013). Trees, Houses and Sidewalk Cities: Child Life and Creative Arts Interventions at a Post-Sandy Shelter. New York Association for Play Therapy Newsletter, January 2013, 16 (2).

“A phone call from a Naval Commander stationed at a shelter in NYC sparked the —- Shelter Creative Arts Therapy / Child Life Initiative Mission. Commander Moira McGuire headed up a mental health team at the shelter serving many families. As a behavioral health nurse, she saw the need for therapeutic activities for the approximately 50 children facing displacement and uncertainty. In response to her outreach, a consortium of Creative Arts Therapists and Child Life Specialists quickly assembled. Our goal was to provide therapeutic creative arts opportunities to children and families post Hurricane Sandy. We hoped to facilitate psychosocial coping and adjustment to the stress and potential trauma of the Hurricane experience and to the stressors of the shelter environment. The first team of volunteers that responded within 24 hours numbered 14 and included 11 child life specialists who were colleagues, alumni or current students from the Bank Street College of Education, along with two art therapists and one dance and movement therapist.

We would like to share some of the techniques that we employed successfully during the two weeks that the shelter was in operation. Leyla Akca, an art therapist, brought paper shopping bags in on that first day. She led children in an activity that explored the “stuff “we carry with us daily, and the invisible stuff we carry on the inside no matter where we are. It was a powerful metaphor, and the children took to it eagerly, decorating their bags with many open-ended materials. Leyla had previously participated in disaster relief in Turkey following earthquakes there. She had a lot of wisdom to share with us all, and her activity gave us focus and purpose.

Maryanne Verzosa, a child life specialist from St. Lukes Roosevelt Hospital, supplied found objects from nature, which included sticks and twigs. As she gathered children in a circle sitting on the floor of the shelter, the children spontaneously created three-dimensional houses out of the materials. One child presented his stick house to his uncle, saying, “This is for you because you lost your house.” Commander McGuire had asked us to bring sidewalk chalk with us, as the children had access to an outdoor patio. Her instincts were perfect. A six year-old boy spent all afternoon creating a chalk city of roads, “for the children”, and buildings. We provided the child with miniature buildings and figures for his chalk city, and the play continued and drew other children into its circle.

One of the final activities took place during the last day when families were moving out of the shelter, many of them to hotels. Tara Lynch Horan, a child life specialist, worked with several art therapists on a community project of building a mural tree and decorating it with leaves representing what families leaned on during Sandy‟s aftermath. The art therapists worked with the children creating the tree, while Tara went from cot to cot, engaging parents in depicting their resiliency factors on precut leaves made from construction paper.

The collaboration of Child Life and Creative Arts Therapists brought about many therapeutic moments for these children and families. The activities employed a variety of directive and open-ended techniques. As we would expect, the children and parents created their own meaning and healing. All they needed was the time, space, materials and gentle encouragement from trained therapeutic agents. Humanity at its best.”

Why Aren’t We Preparing Kids for Disaster

Guest Blogger Heather Beal is a military veteran with 23 years of crisis management and operational planning experience that she draws upon daily in her battle to raise two well-prepared, happy, curious, and intelligent children. As a trained emergency manager and parent, she saw the need to provide age-appropriate disaster preparedness information to young children in a way that empowered rather than frightened them. She is currently writing additional books to cover a greater spectrum of potential disasters children may face.

Guest Blogger Heather Beal is a military veteran with 23 years of crisis management and operational planning experience that she draws upon daily in her battle to raise two well-prepared, happy, curious, and intelligent children. As a trained emergency manager and parent, she saw the need to provide age-appropriate disaster preparedness information to young children in a way that empowered rather than frightened them. She is currently writing additional books to cover a greater spectrum of potential disasters children may face.

“Generally speaking, we do not prepare our children for disaster. We make them hold our hand in the parking lot and talk about the dangers of getting burned by the stove, but we stop short of this really big “disaster” word. When I think about it, I can come up with a few excuses we call reasons as to why we don’t give this topic the attention that we should.

First, like our children, (but usually without donning the superhero capes and masks), we believe that we are invincible. It (the disaster) can’t happen to ‘us,’ it only happens to ‘others.’ Folks – look at Hurricane Harvey, Superstorm Sandy, Hurricane Katrina, the Indian Ocean Tsunami, and any other number of disasters. With that many people affected – the ‘us’ and the ‘others’ are the same people. We need to look at disaster as a probability, not a possibility.

Second, we think talking about disaster will be too scary. I get it. No one wants to tell children anything bad could happen. We all know our children could get terribly hurt running if hit by a car in the parking lot, but we don’t get into explicit details about injury and death. We do however, talk to them about being safe, making good choices, and not doing things that could more likely result in their getting hurt.

We should approach talking about disaster in the same way we approach other learning topics or the consequences of actions or inaction. We don’t need to focus on the destruction a tornado can cause, how their lives could be uprooted, or what other things could dramatically change. We can however, talk about what children need to do to stay as safe as possible.

There are no guarantees in life for anything. We can’t guarantee that a car in the parking lot won’t do something stupid, just as we can’t guarantee the tornado will miss a child’s house, school, or childcare. But we, as parents, as childcare providers, as educators, as caregivers, as emergency managers, and as community members, can arm our children with the tools to succeed. We owe them that.

Sounds good – but how would I know, right? Fair question. A few years ago I tried to explain to my then 4-year old daughter that she and her brother might be woken up in the middle of the night to go into the basement if there was a tornado warning. Of course, it was already dark and stormy (thunder and lightning and everything). Needless to say, I did a very poor job, ultimately scaring her and beating myself up about my failed attempt to mitigate later fear through a botched explanation. Never again I vowed.

That was when I discovered that almost no one was having the conversation with young kids (toddler, preschool, or kindergarten) about disaster. At the same time, I realized that disaster was not going to sit by patiently and wait until my children could calmly and rationally discuss everything at a grown up level. I decided I could develop a way to talk with them in a way that didn’t scare them, but instead empowered them by teaching them what to do and giving them back a little control in a typically uncontrollable situation. They might not be able to stop the disaster, but they could do something to increase their safety within it.

I started Train 4 Safety Press to develop picture books that would teach children what to do “if.” As I conducted research, I discovered a few books out there on the science of disaster, but almost none that taught young children what to do when the disaster was happening. Our first book Elephant Wind tackles what to do during a tornado. Tummy Rumble Quake teaches children about the Great ShakeOut™ and earthquake safety.

Children have a great capacity for building their own resilience. Teaching them how to protect themselves can have an exponential effect. Children could not only help themselves, they could help their classmates, their teachers, their family and their community. Isn’t anything that increases the odds we bring our children home after a disaster worth it? Can we afford not to talk about it?”

And here is a great resource: National Child Traumatic Stress Network

Empowering Kids Through Writing: Spotlight on Little Legacies

The Children of Chanov and Lidice

During my recent travels to the Czech Republic, I had the opportunity to learn about two populations that I knew little or nothing about: the children of Lidice and the children of Chanov. Our hosts, Jiri & Marketa Kralovec of the Klicek Foundation, arranged a day long outing to honor one group and to serve the other.

A few days prior, Marketa had given me a book

that told the story of the massacre of an entire village during World War II. It is a chilling and heartbreaking narrative of the fates of 82 children between the ages of 1 to 16. In response to the assassination of Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich in 1942, the Nazis sought retribution by shooting all the men of Lidice (aged 15 and up), transporting the women to concentration camps, and murdering the children en mass by gassing them in a truck. Not even the dead were spared, their graves looted along with everyone’s homes and businesses, before the Nazis burned everything to the ground.

We arrived at the historical site of Lidice, the midday sun unrelenting in the early Spring heatwave. We made our way over rolling green lawns to the memorial (Pamatnik Lidice) that overlooks the expanse of land where the village once lay. No book could have prepared me for the impact of the life-sized collection of sculptures embodying the 82 murdered children. I stood before them and wept for these children and all those murdered during the Holocaust. I wept at the cruelty of human beings. I wept for the legacy that lives on in the DNA of my life partner, his parents having survived Auschwitz at the tender ages of 12 and 15. They could have been these children. In some ways, they were.

The artist Marie Uchytilová created the memorial in the 1990’s, but died before she was able to complete the sculptures. Jiri described paying a visit to their friend, Marie, during her selfless work. The haunting presence of the children’s likenesses in the fading light cast shadows as they drank tea and chatted late into the night. “She informed us that she often spoke to the children as she crafted their images,” Jiri said. “And she tried to find out everything she could about each one, so that she could truly fashion their souls.”

We left the children and walked in silence back to the van. We traveled on, stopping for a tour of the pediatric ward of a hospital before moving on to the last leg of our journey. We had little idea of what awaited us as we drove north west to Most in Bohemia and the Chanov housing estate. Of course Marketa had told us about our upcoming visit. Borivoj, (all names of patients and children have been changed to protect their privacy) a brain cancer survivor, had attended the Klicek summer camp as an ill teen. Marketa and Jiri stayed in touch with Borivoj and his family, visiting them occasionally over the years. On one such visit, Marketa took notice of the many children of the neighborhood, hanging out with seemingly little to do. She was moved by their plight, and vowed to return to set up an afternoon of play on a monthly basis.

“No one goes there,” she said as she prepared food for our day’s journey. “It is the poorest and most dangerous part of the Czech Republic. If people do go there, it is to make themselves feel better, handing out candy and toys, and getting back in their cars, not really just being with the children or connecting with them.” As Marketa described the situation, I thought of the untouchables in India.

According to Wikipedia, “[t]he Chánov housing is these days perceived by many Czechs as among the worst examples of ghettoization of the Czech Romany population and has been described as “the housing estate of horror”, “a hygienic time bomb”, “a black stain” and the “Czech Bronx”. The Roma tenants of Chanov fare dreadfully in today’s Czech Republic, relegated to institutionalized country-wide discrimination, racism, marginalization and poverty. The Roma are largely unemployed. 94% of the people have only a primary education, if that. 38% of the population are children under the age of 15.

Word of our coming had spread, and over 60 of these children and their parents greeted us as our van pulled up in front of the Chanov school, skirted by an astroturf football field. The children gathered eagerly and Marketa divided them into two groups, challenging them to a contest.

“All right!” she coached them. “Let’s see who has better English, the boys or the girls!” I was the designated judge, and the girls surrounded me eagerly. “My name is Anuska,” piped up one girl sporting polka dot shorts and a bright pink t-shirt emblazoned with the head of a blue giraffe. “What is your name?” “What color are your eyes?” “One, two three…” Other girls chimed in, counting up to fifteen with pride. “How old are you?” asked another. Then, they all started to sing, “Head and shoulders, knees and toes, knees and toes!”

The boys jockeyed for attention, keen to tease and one up one another in the process. “My name is…” began one, and several interrupted to shout him down with their own introductions. They jabbed and pushed one another, joking and laughing and even yanking down one boy’s shorts as they showed off their skills. Definitely a different energy than the girls!

Capitalizing on the bit if English they knew (way more than my Czech, I might add!) I asked the children to show me some of their games, awkwardly pantomiming patty cake. After humoring me by joining in, the girls broke into a much more intricate version, clapping their hands in a fast paced rhythm that left me in the dust. Then the kids introduced me to the game Baba (If I am spelling that right). Figuring out the rules was easy, as they ran up to me, tapped me none to gently on the back, yelled “Baba!” with great enthusiasm, and ran away from me. Oh, the Czech version of tag – I get it! In fact, there are many games that translate across cultures.

The children eventually broke off into smaller groups, some to draw on the parking lot with colored chalk that Marketa had brought, and some to start up a game of soccer. The play specialist volunteers set up a makeshift hair salon, brushing the girls’ hair and styling both boys and girls alike using many mini rubber bands.

Several children showed us their dancing skills, and my colleague, Marifer Busqueta from Mexico City, engaged them in a few Latina moves.

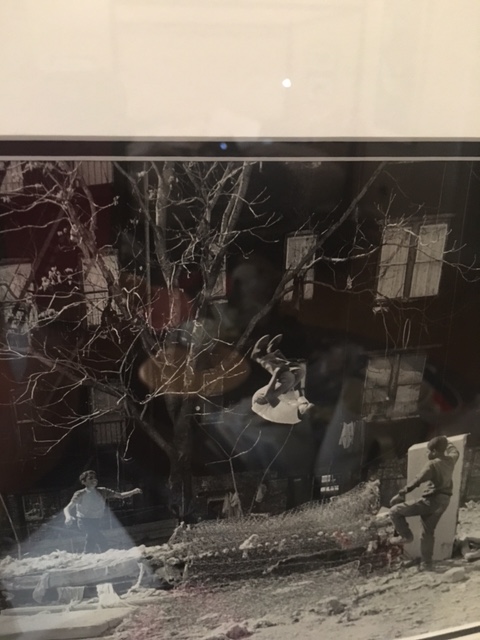

One group of boys made their way to a large sand pit at the edge of the football field. They dragged over two box springs, the rusty inner workings of mattresses, piling them up to act as a springboard for their acrobatics. And so the real show of the day began. The boys, singly and in pairs, ran pell mell at the springs and leapt upon them, catapulting themselves into the air in arching flips and tumbles. They showed no fear, but my heart beat fast and hard in my chest as they flew past me, landing triumphantly in the sand. I couldn’t help but think of the framed photograph hanging in my bedroom back home of children in a 1980’s South Bronx performing similar feats of daring.

Towards the end of the day, Jiri Jr. corralled the kids into the cement bleachers to pose for a group photo. There was homemade gingerbread for all, and one child split her treat in half to share with Marifer, before enjoying the sliver left over for her. We spent 4 hours altogether with the kids, before collapsing exhausted into the van and heading home to the comforts of Malejovice. Hot running water and electricity would greet us, although no such luxury awaited the children of Chanov. The joy of a day of cross-cultural play with wonderful kids lay juxtaposed in my mind with thoughts of children in historical and current contexts. When hate and racism allow us marginalize, ghettoize, and incarcerate a segment of any population, keeping them from sharing in the most basic of human rights (employment, access to medical care, decent living conditions and education), how far are we from enacting the fate of the children of Lidice upon our own children?

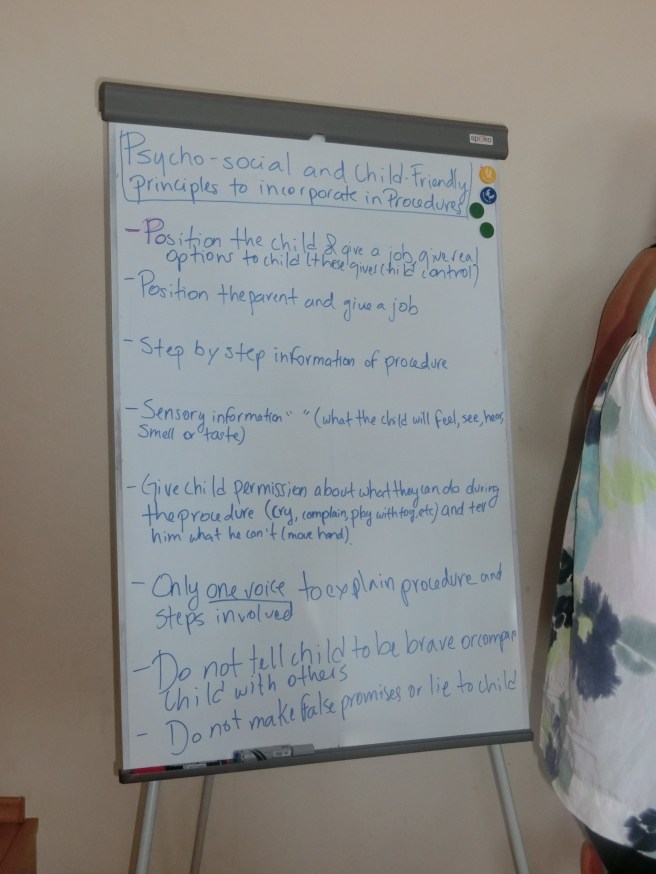

Child Life & Nursing: Practicing pediatric psychosocial support in Novy Jicin

My recent visit to the Czech Republic, sponsored by the Klicek Foundation, included a return to the Mendelova Nursing School in Novy Jicin. This time, Maria Fernanda Busqueta Mendoza joined us from Mexico, and 50 students participated in our seminar, making it a great opportunity for global learning and a multicultural exchange of ideas. As you can see from the first photograph, the students were a lively bunch, and they eagerly participated in the highly interactive time we spent together. Jiri Kralovec served as our interpreter and his son, Jiri, touted by Foto Video Magazine as this year’s hottest photographer on Instagram, documented our learning. Most of the photos below are his work.

Jiri and his wife, Marketa, started us off by sharing information about the importance of play for hospitalized children and the history of their efforts to bring hospital play to the Czech Republic. It has been a slow, uphill battle to change the hierarchal and disempowering bureaucracy of their medical system. I followed with an introduction to the field of Child Life, the role of child life specialists in hospitals, and the possibilities for collaboration with nurses. I spoke about the role of play and community in the healing process, before moving on to some illustrative activities.

Sharing our own memories of play is one way to deepen our appreciation for the role of play in our lives and in the lives of children. I asked the class to think about their own childhood memories, using their five senses — what do they remember about their play environment? Did play occur inside or outdoors, or both? Were they playing alone, or with others? Did they play with toys, loose parts, or their imaginations? Are there sounds, smells, tastes or textures associated with their memories? What feelings are evoked in sharing them? The students paired up and took turns both sharing and listening to one another.

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

Armed wth a deeper awareness of the value of play, the students were now ready to learn a bit about how to make procedures less frightening for children. I have always wanted to use role play as a way to demonstrate all the things that can go wrong during a procedure, and how minor changes can make things easier for medical staff, children, and caregivers. I took this opportunity and asked for volunteers. One young man played the patient. We instructed him to lie down and asked three others to pin him down to the table, much like medical personnel are likely to do when a child receives an IV. We demonstrated how the very act of being forced into a prone position increases one’s sense of vulnerability and loss of control.

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

Add to that several adults talking at once, loudly over any protests you might make, telling you to stay still, not to cry, to be a big boy, not to look…. and you get the picture. Chaos, stress and shame accumulate to make for a disastrous experience for all.

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

But there are some simple things that nurses can do, either alone or in partnership with play specialists, to change the outcomes of such procedures. It doesn’t mean that the child won’t cry, but it is more likely that the child won’t suffer emotional trauma, will return to baseline quicker, and the nurses can feel more successful and less like they are causing the child undue suffering.

With these tips in mind, the students enacted a better case scenario, where the parent has a supportive role in positioning the child for comfort. The child is upright and held in a calming hug, rather than being restrained on the table. The child is given some choices, such as which hand to try first for the IV (the non dominant hand is preferable), and whether to watch the procedure or use a toy or book for distraction.

- Electing one person to be the voice in the room,

- encouraging the child to breathe deeply and slowly,

- narrating each step of what the child will feel,

- explaining how a tiny plastic catheter, not the IV needle, remains in the child’s hand to deliver medicine,

- staying away from comparative or shaming statements,

- and showing empathy

are all ways to provide psychosocial support, making the experience less traumatizing and painful for the child. Accumulated painful and traumatic medical experiences can make children phobic and avoidant of medical care.

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

We also spoke about non-pharmacological pain prevention and reduction. The interactive component of our lecture surely made our important information memorable. The action and laughter surely made more of an impression than a power point! We all reflected together about how even adult patients can benefit from choices, information and empathy.

Back to the topic of play, we explored ways for the nurses to instill playful interactions into their communication with pediatric patients. Rapport building and distraction through the use of hand games is one way that they can put a child at ease. I demonstrated several hand games, and asked them to show me some of theirs as well.

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

Our time with these wonderful students ended all too soon. We posed outside of the school for a photo with some of the Klicek Foundation hospital play specialists before heading to the historic square down the street. Around every corner of this country is a beautiful scene, no matter where you are!

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

(photo by Jiri Kralovec)

Restoring my Soul: Recipe for Self Care in The Czech Republic

We all need time to restore our energy and feed our spirits. It is not an easy task during the workaday world of most of our lives. For anyone in the service professions, self care is a necessity, not an option. As a professor teaching Child Life graduate students, my calendar revolves around the academic year, and by the time the end of May rolls around, I am usually quite exhausted and spent. An invitation to teach in the Czech Republic came at a very good moment for me – after graduation and at a beautiful time of year.

Recipe Ingredients:

Knowing what to expect

The recipe for filling my well was a simple one, but I could not have done it without the friendship and nurturing of the Kralovec family. Marketa graciously and painstakingly created a hand written and illustrated book telling the tale of all we would be doing together in the next two weeks. The guide was especially helpful in letting me know what to expect, as we traversed the country and visited Poland and Austria.

A Warm Welcome

But the whirlwind began with a gentle, warm welcome back to Malejovice, the home of the Kralovec family and the Klicek Foundation Hospice. My third excursion from New York City to the Czech Republic felt like returning to the home of my soul. Marketka, their daughter and a highly skilled artist, documented my arrival by depicting the short emotional distance between our two homes. What’s an ocean anyway when like minds and hearts connect?

Bright and cozy bed linens and wild flowers from their garden greeted me in the guest room. The sounds of the birds sifted in with a gentle breeze through the open window.

Wonderful Home Cooked Meals

Each meal was prepared from local ingredients and cooked with love. The eggs from their chickens (rescued from terrible conditions in a chicken mill), fresh herbs from their garden, homemade soup, duck with dumplings and sauerkraut, fresh bread and danishes, black tea and local beer…….. my palate fairly exploded from the goodness of it all. The family would not allow me to wash a plate or rise for a napkin. The nurturing wasn’t just about the food, but the care with which they served it.

Four Legged and Winged Friends

Animals are therapy, and a wide variety of animals inhabit the pastures surrounding the 100 year old schoolhouse. Each morning began with a chorus of birds at about 4 AM, followed by the harsh and comical braying of Donkey (his name is Donkey) at 7 AM. The sheep served as the snooze alarm, sounding off a few moments after Donkey. Mollie the dog was the night time alarm system, and the chickens cooed and clucked whenever we approached them. The cats draped themselves over windowsills and plant boxes and moseyed up and down the driveway throughout the day.

Nature

Nature is what grounds us and reminds us of the cycle of life, our smallness, and the beauty of creation. The surrounding forests of Malejovice, the wild flowers and rolling hills and pastures, the lush ponds and hidden villages of the country……… all served to quiet my gerbil wheel mind.

Solitude

I get plenty of time alone teaching online from my apartment, but there is something different about being alone with nature in wide open space. Nothing to distract me from the sun, breeze, scents and light.

Wonderful People

Solitude is always best when you return from your walk to a household filled with joy, love, laughter, and music. The time spent with these people, and all the people we met on our travels, energized me and acted as a balm to my tired soul. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you – and these words will never be enough to convey my gratitude.

Instructions:

Repeat whenever able.